Inflation in Germany: where the price increases come from

- By sennenqshop/li>

- 698

- 02/09/2022

You can find more business topics here

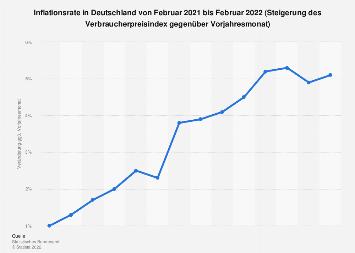

Life in Germany has become more expensive: Post has increased postage, the prices for vegetables in the supermarket have attracted, even when it comes to heating costs, you have to dig deeper into your pocket.

With over five percent recently, the inflation rate in Germany achieved the highest value in three decades.The Germans are worried about their financial security.

The concern that triggers this price increase in the Germans is even greater than that of Coronavirus pandemic and Ukraine crisis.At least that is the result of the "Security Report" from the Center for Strategy and Higher Leadership and the Institute for Demoscopy Allensbach.

Inflation worries the Germans

A total of 1090 Germans aged 16 and over were interviewed in January.70 percent stated that they were worried about the strong price increase.

Every second feels personally threatened with the consequences of inflation - a year ago it was not even every third."The current price increase is very high in comparison to what we have experienced in recent decades," says economist Karl Brenke.

You can see the same phenomenon but also in other countries of the euro zone and in the USA.There, inflation was even seven percent at the end of the year.

Increased energy prices as the cause

"The decisive factor for these inflation rates is energy prices," says expert Brenke.The prices for crude oil and gas would hit hard and drove the inflation upwards in the individual countries.

Economist Kerstin Bernoth also sees it that way."Geopolitical conflicts such as the tensions with Russia play a role in energy prices, but the energy transition is also currently making fossil energy more expensive," she says.Brenke confirms: "German politics is currently focusing on increasing fossil energy prices, CO2 taxation has taken place at the beginning of the year".In Germany, the state also pushed the inflation further.

In the current situation, the government could hardly do anything about the price increase in oil and gas."You can only wait and see that the saber rattling from Russia and diplomatic solutions are found," said Brenke.

Expert Bernoth also says whether the previously sectoral price increases, such as in the energy sector, is a broad base in Europe..

Rising prices: there is no room for almost every second

Der Anstieg der Verbraucherpreise schränkt den finanziellen Spielraum vieler Menschen ein. Manche sorgen sich, dass sie ihren Lebensunterhalt nicht mehr bestreiten können.Pandemic also plays a role in the price increases from an expert perspective."There are and existed in several sectors," recalls Bernoth.The lack of computer chips in particular was quoted, but there is also no other material in the processing business.

Sneakers and bicycles can be affected as well as dishwasher and car spare parts.Production and logistics capacities were shut down in the Lockdown, and companies did not come after the rapidly attracted demand.

"The households saved a lot during the pandemic because they couldn't spend anything in the Lockdown.A strong demand due to the recovery after pandemic and savings now meets a bitter offer, "analyzes Bernoth.Often there is still a problem with transport - there is a lack of ships and containers, the freight rates have risen.

Brenke suspects that another factor could affect the situation: "The minimum wages will be raised by six percent in Germany this year," he recalls.

Since the beginning of the year, the minimum wage has been 9.82 euros per hour, in the second half of the year it increases to 10.45 euros.A draft law of the Federal Ministry of Labor still provides for an increase to 12 euros in 2022.

Caring about price-wage spiral

Brenke sees jobs in danger."The initial introduction of the minimum wage was with a relatively low inflation, so consumers also accepted a minimum wage," he looks back.

The Germans nevertheless went to the hairdresser as often, had not dispensed with taxi rides or terminated newspaper subscriptions across the board.

"If the minimum wage increase now takes place in an environment, consumers have to pay more attention to their expenses," explains Brenke.Some should then reduce their expenses - and that in turn could cost jobs.

Higher prices from higher wages

"It would also be a problem if the high inflation would lead to a price-wage spiral," warns Brenke.This means the following scenario: The unions are calling for higher wages due to increased prices.If an employer has to pay more to his employee, this again leads to higher prices in the end.

"If the price increase that is now coming from the outside is used by unions to enforce higher wages, then inflation later comes to a considerable part from the inside," says Brenke.

In front of the German government, however, the experts see another player: "The central banks are mainly responsible for price stability, which is not the mandate of the state," emphasizes Bernoth.Politics can intervene sectorally and temporarily reduce taxes on certain products or pay certain grants.

Households with low income are disproportionately affected by inflation."Politicians can set itself the task of doing something that there is not so many households at the subsistence level at all," says Bernoth.

ECB could raise interest

Inflation must be taken very seriously."The central banks must now be very vigilant in the coming months and, if necessary, act," emphasizes Bernoth.

Here there are still doubts as to whether and when the European Central Bank (ECB) will raise interest rates."If the general price level and wages continue to increase in the coming months, this should be necessary," estimates Bernoth.

When the prices will fall again - the experts can also predict this difficult."There are very great uncertainties," says Bernoth.The production jam will soon be a bit, and there is still no improvement in the case of energy prices."The prices will tend to be declining in the course of the year," she estimates.

Über die Experten:Prof. Dr. Kerstin Bernoth ist stellvertretende Leiterin der Abteilung Makroökonomie am Deutschen Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Berlin und lehrt an der Hertie School of Governance Berlin. Die Forschungsinteressen der Wirtschaftswissenschaftlerin liegen im Bereich empirische Finanzmarktforschung, Geld- und Fiskalpolitik sowie Finanzstabilität.Karl Brenke ist wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter in der Abteilung Konjunkturpolitik am Deutschen Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Berlin (DIW). Er studierte Soziologie, Volkswirtschaftslehre und Statistik an der Freien Universität Berlin.Used sources:

Todesfall