The style of Senegal | Fashion & Clothing

- By sennenqshop/li>

- 1022

- 11/04/2022

The internationally successful fashion designer Adama Paris dresses stars like Beyoncé. In doing so, she also paves the way for young creative people in her home country. A report from Dakar by Gabriel Proedl (text) and Hien Macline (photos)

The queen is expected. A chauffeur brought her here, on Rue Corniche in a poor area of Dakar, Senegal. It is the hometown of designer Adama Ndiaye. The international fashion scene knows the 45-year-old as Adama Paris, here she is known by her aristocratic title: "Queen of Fashion".

For the first time in a long time she is visiting from the French capital. The daughter of a diplomat grew up in Paris, where she learned tailoring, founded her own label and achieved international fame. And always kept in touch with Dakar. She wants to stay ten days in the city, which has become the center of the West African fashion scene thanks to her.

She has a boutique on Rue Corniche in the far west of the city. The portal is made of colorful corrugated iron, and clothes from her collection are on display in the shop windows. The Muslim cemetery lies behind a four-lane road, with the sea beyond. It is a few hundred meters to the westernmost point of the continent. Adama Paris enters the store, her employee Fatou has previously swept the dust for a long time. It smells of exhaust fumes and Jean Paul Gaultier's perfume "So Scandal".

When she opened the boutique 17 years ago, not even a street led through the district. In the meantime, photographers and designers have settled nearby. But the greatest gift to her country is the "Dakar Fashion Week", which she organized for the first time 20 years ago - at the time the first event of this kind on the African continent. Now Dakar is the capital of fashion.

Fashion in Senegal: There is also a “Black Fashion Week”

Adama Paris is internationally successful and dresses stars like Beyoncé. Her own TV channel "FA TV Channel" is broadcast in 46 African countries and broadcasts "Fashion made in Africa" 24 hours a day. Her “Black Fashion Week” is now traveling around the world from Dakar, to Brazil, Montreal, Prague and Paris, right there on the Place Vendôme, between the Ritz luxury hotel and the Chanel boutique. "I had my stage for 20 years," says Paris, "now I want to show others how to take the stage."

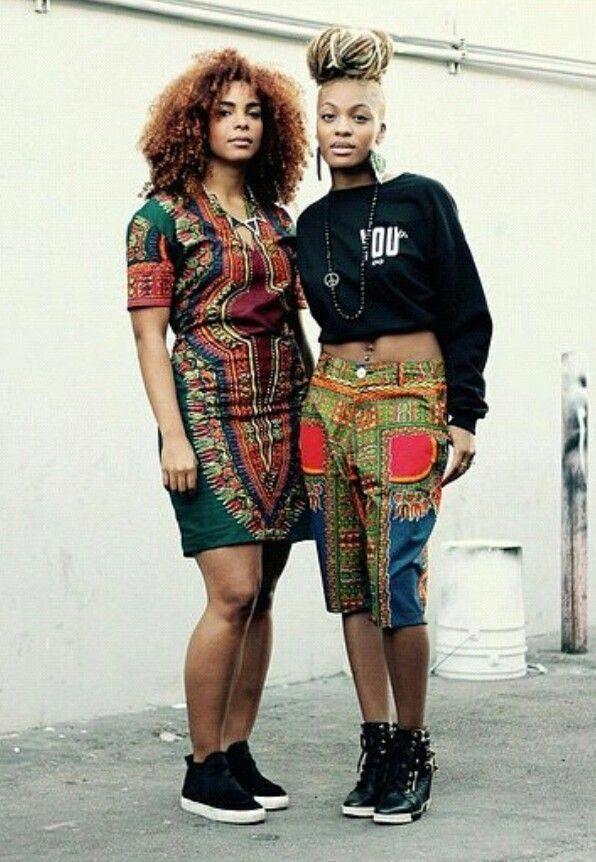

On some days, the streets of Dakar seem like a public catwalk: women and men stride in elaborately embroidered boubous, rectangular pieces of fabric with an opening for the head that are slipped over the body. They also wear colorful, elaborately woven headscarves. But also recycled clothing, extravagant designs, high heels and transparent tops.

Thanks to designers like Adama Paris or Oumou Sy, the 70-year-old grand dame of fashion in Senegal, the scene is also becoming internationally known. They inspire and support young creative people and help found companies. More and more Senegalese artists and musicians deliberately do not wear fashion from Europe, but have individual pieces made in their own country.

Loumou Evans wants a great career - like Adama Paris

One of the hip designers is 22-year-old Loumou Evans. Last year he equipped almost all major music video shoots in Senegal. He is already a star in the Dakar art scene. Compared to Adama Paris, his career has just started. He wants to learn from the greats like you.

There has been a burst pipe on the street from Loumou Evans' studio, and the water is ankle-deep. Women pick up their shoes, raise their boubous, and wade through the muddy waters. Evans balances over a concrete ledge toward a heavy iron door and bolts it. Tables, chairs and boxes are stacked in the room where his aunt wants to open a restaurant. Until then, Loumou can set up his studio here rent-free. “Fattah!” he says to his younger brother, “turn on the fan. It's hot again.” “I wanted to save some electricity,” says Fattah. The room has no windows, only a large door, but even that is always closed. "I want to work undisturbed, I don't want anyone to know that I'm revolutionizing the fashion scene from here," says Evans with deliberate exaggeration. He has pasted a complete edition of the French "Vogue" on one wall: "At some point I want to go in there too."

Young creative people in Senegal: hoping for a breakthrough

He looks at his smartphone every few minutes. 27,700 people follow him on Instagram – customers and well-known artists from Senegal and West Africa. Anyone who sees his account would think that Loumou Evans is the creative director of a French label with its own production and various departments from advertising to distribution. Few know that everything he makes is created here in this small studio. Without employees, on a single old sewing machine. His assistants: brothers Shal and Fattah, 16 and 18 years old. This is also where they live and spend the night, on narrow camp beds between the editing table and clothes rails.

Loumou Evans did not learn in a studio in the French capital like his role model Adama Paris, he learned on the street. With seamstresses who set up their sewing machines at numerous house entrances in his neighbourhood. Evans watched her since she was a child; at the age of nine he began to sew for fun with his grandmother's old machine. Later he did unskilled work for his aunt, herself a seamstress: he sewed narrow lengths of leftover fabric into larger pieces, from which the aunt made shirts and boubous. "Everyone in my family can sew," says Loumou Evans, "but everyone makes traditional clothes." In Dakar, this means that seamstresses place a machine in a small stall on the street or work side by side in market halls. All are independent, there are hardly any mergers or joint studios. They make commissioned work, all one-offs, sew boubous for baptisms and weddings.

The fashion scene in Dakar is growing

When Loumou Evans left school a year before graduation, that's what he would become: a tailor in a large market hall like that of the well-known Marché Sandaga, where fabrics and yarns are stacked to the ceiling, cords are twisted and fabrics are woven. His aunt advised him to go there. In the same year he was given his grandmother's sewing machine; because he was shy, he didn't dare to go into the hall. He opened his first small room. He kept the door locked.

His aunt introduced him to the cloth merchants and weavers, taught him how to negotiate in the market and set prices in the shop. "Know your street," she advised him, "at first, work for pocket money until people know what you're capable of." In the beginning, she even let him take part of her clientele. Evans made money quickly - mostly on touch-ups. His aunt was happy. She considered handing over all her contacts to him and opening a restaurant. But Evans refused. He chose to be different than a traditional Senegalese tailor.

Loumou Evans has hardly slept in three days. He wipes the sweat from his square face. "I'll do anything to be successful," he says, "I work non-stop - when I grow up I want to be as famous as Adama Paris."

Fashion in Senegal: inspired by stars like Beyoncé

Evans felt early on that he was different. As a youth he was shy; his means of showing his personality became clothing. Once, about three years ago, he says, he wore an outfit he sewed himself for the first time. He shows pictures on his smartphone: black sneakers painted with red paint, the signal strips of a high-visibility vest stuck over his pants. A jacket patched together from old scraps of fabric. "People thought I was a star. When I told them I was from Dakar, they didn't want to believe me.” That may be because Evans is inspired by stars: he follows music greats on Instagram and studies models on the Adama Paris TV channel. He doesn't want to be famous himself, he says, but his label should be internationally successful. "Nobody needs to know my face, but my clothes do," he says. "I want a real label in Europe or North America, like Gucci. They make bold designs.” He wants employees and sales, a website and an advertising campaign. “But I have no idea how to do that,” says Evans. "You have to go to school, my friend," says his brother Fattah.

Evans turns on music. He sits down at the sewing machine and pulls out his cell phone. He received a video message, the video shows: "Good evening dear Lou. I'll send you photos so you know what kind of shirt I want.” In Senegal, communication often takes place via Instagram and other social networks. Messages are written and even telephoned about it. Most companies completely do without classic websites - an Instagram channel is sufficient. This is how it works at Loumou Evans: Customers discover his account through recommendations from friends and send clothing requests via chat. Evans fulfills the order, packs the finished piece into a bag and ships it using parcel services. Payment is made via Paypal or bank transfer.

Adama Paris is interested in the designs of young creative people. About Loumou Evans she says: "He is talented!" Many try to get an internship with her. Paris chooses according to hard criteria. She only agrees to whom she thinks is capable of an international career. If possible, they complete the internship not only in Senegal, but also in Paris, where the main location of their boutiques is near the Place de la Bastille. Senegalese designers drop by there every now and then. “Everyone wants to go global but don't know how the market works outside of Senegal. How could they?” asks Adama Paris. A fashion school, for example, teaches much more than making good fashion. She teaches to think big: "A good tailor does not have to learn tailoring from others. He learns that on his own. He has to learn to make something bigger out of his talent.”

"We need to free ourselves from Western thinking," says designer Adama Paris

Europe should not remain the only chance for a breakthrough. For years, Adama Paris has been looking for investors for her biggest project to date: she wants to build a factory near Dakar with 100 employees. “We only want to produce what we sell, and the working conditions should be as good as in France.” Later she says: “I want to build a scene here in Senegal – if we don't do it, who else will? We shouldn't be dependent on help from Europe – we don't need pity.” Adama Paris wants to boost her home country's self-confidence. Corona could help her: Many rich people no longer bought in Paris or Dubai, but went to the local tailor. Paris also says: “We have to redefine success. After all, who decides that a breakthrough can only be achieved if you have boutiques in Paris, London and New York? That's western thinking!”

In his studio, Loumou Evans continues to work on his sewing machine. He tells how he photographed his collection with models for the first time. He advertised a casting on Instagram, for which more than 100 models applied. Evans chose Marina, who lives just a few blocks away. Coming from a Christian family of eight, Evans is strictly Muslim. The two have been close friends ever since.

But a short time after the casting, his mother fell seriously ill. She was taken to the hospital and died a few days later. To this day, Evans doesn't know why. He stayed behind with his two brothers, whom he now has to look after alone. His eyes drop to the ground. His carotid artery is pulsing. Above that are his tattoos, which he had done after the death of his mother.

A big A for Awa, his mother. An F for Fattah, an S for Shal. That's what his label should be called from now on: AF-Shal. "I thought about quitting everything. But that wasn't possible, I had to take care of my siblings. I did the shoot with the models two days after her death.”

Up-and-coming designer Loumou Evans works day and night for his big dream

Evans picks up his cell phone and calls Marina. 20 minutes later she is in the studio. A slim, erect young woman. She models for Evans - and for Evans biggest idol, Adama Paris. Marina has already walked for her twice at the Dakar Fashion Week. Evans has never been there. But he knows designers who have made the leap as a result. Suddenly investors take notice, or European companies invite you to do internships. Evans dreams of a bigger workshop, more sewing machines and employees. Marina should be the first employee, he has already promised her that.

In the evening in the studio he oils his sewing machine, cleans it and tightens the V-belt, pushes the pedal to the limit. It sounds like a small broken motorcycle. Evans threads thread and starts designing without a single drawing. So he will work until the next morning. Meanwhile, his two brothers will sleep on narrow cots next to the sewing machine in bright light.

The research was funded by the European Journalism Center and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.